Isn’t there a danger of over-intellectualising? … Art challenges and it challenges the status quo, and if you’re left wing that’s what you do, and if you’re on the political right generally and you’re a conservative you like things as they are.

Justin Webb, 8 November 2013

Justin Webb, presenter on the BBC’s flagship Today programme (which is broadcast on its premier station, Radio 4), put forward a highly controversial point this week: he thinks the BBC’s impartiality might undermine its ability to report the facts. It is very surprising for a journalist to argue that factual accuracy and impartiality are opposed; such a claim may indeed alarm those who already question the BBC’s impartiality. Webb’s latest intervention is certainly revealing in its own right, but what may surprise readers are the transcripts which I have made of the many, apparently unconscious and sometimes astonishing demonstrations of left wing bias which Webb has openly displayed while presenting on Today. These transcripts, which I reproduce below, show that Webb’s recent comments about the BBC’s impartiality are part of a well-established pattern of “partiality” in Webb himself.

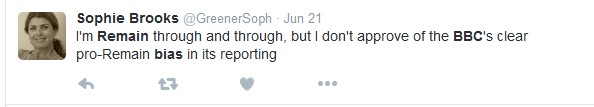

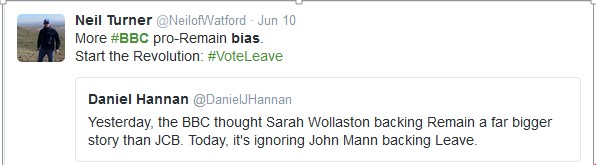

Webb’s latest comments focus on the BBC’s reporting of the European referendum, which many feel was heavily biased in favor of Remain.

I think Leave had good cause for suspicion. For example, the BBC were diligent in reporting on celebrities like David Beckham who supported Remain (despite what many would regard as the former footballer’s tenuous grasp of the issues involved), but were virtually silent on the intelligent and well informed support for Brexit from actor John Cleese and novelist Dreda Say Mitchell. Cleese and Say Mitchell’s stance may have been difficult to accept for their Remain supporting “luvvie” admirers, which is perhaps why the BBC’s audience might have gone through the entire referendum without realising that this famous pair supported Brexit. The BBC even featured Remain ads on its website (see http://order-order.com/2016/05/16/proof-remain-campaign-is-paying-bbc/), which it lamely blamed on “third party” error.

Webb’s article in this week’s Radio Times however argues that the BBC was too impartial, and that this excessive impartiality somehow disadvantaged Remain: “Some of those on the losing side think they were let down. The Oscar-winning film producer Lord Puttnam is among those who wonder if impartiality rules torpedoed the search for truth: he accused the BBC in particular of providing ‘constipated’ coverage.”

This quote illustrates both Webb’s qualities and his terrible weaknesses. He is well intentioned and sincere, and not afraid to voice an opinion. His bias is not deliberate or malicious. What is frightening is how unconscious he is of that bias; his political views are so deeply ingrained that he regards them as simply corresponding with objectivity; he is unable to see the world from a different perspective and therefore unable to achieve any awareness of the political assumptions which underlie his own views.

In this particular case, Webb suggests that impartiality may have prevented the BBC from challenging some of the claims made by the Leave campaign which were – so the Remain camp claim – factually incorrect. These disputed claims essentially consist of the claim that £350m is paid by the UK to the EU every week, and that this figure would be spent on the NHS post-Brexit.

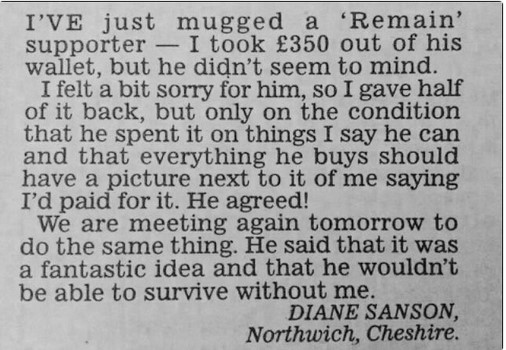

Indeed, £350m is a gross figure, and does not take the UK’s rebate or the amounts paid by the EU to the UK into account. And, indeed, how the money formerly paid by the UK to the EU is spent post-Brexit will be decided by parliament, not by the Brexit campaign; parliament may, indeed, not decide to allocate an extra £350m to the NHS. But these are strange arguments to make against the value of objective reporting, which is a sacred value. Most supporters of the Leave campaign understood that £350m was a gross figure. It was well understood that around £163m was the net saving, and the remaining c. £187m was money that the UK could now spend as it chose, not as the EU dictated. The Brexit campaigners even joked about it:

And most Leave voters understood that the NHS was one area to which previous EU contributions might be allocated, but that it would be up to the government of the day to decide this. All politics relies on tangible images and concise slogans. The campaign to Leave Europe was no exception.

The Remain campaign for its part made claims which were arguably even more questionable. George Osborne claimed an emergency budget with tax increases and spending cuts would be required post Brexit. This silly proposal, though unchallenged by the BBC at the time, was immediately shelved after the referendum. Remain’s main argument was that institutions like the IMF, the IFS and the Bank of England predicted that there would be serious negative economic consequences if the UK left the EU. Not once did the BBC detail or analyse the appalling forecasting track record of any of these institutions, which undermined the value of any argument made with their support.

My view on the claims of both sides is of course partial and open to challenge. What is notable however is how Webb approaches them as a supposedly unbiased journalist:

- He believes he knows the truth in this particular case;

- He believes the truth contradicts the Leave campaign’s claims;

- He doesn’t credit Leave voters with a mature understanding of the Leave campaign’s claims;

- He doesn’t see the inaccuracy of the Remain campaign’s claims which the purportedly objective BBC did not subject to scrutiny;

- He thinks that to present the truth you may need to abandon impartiality;

- He doesn’t credit the audience with an ability to weigh up the claims made by both sides without the assistance of an expert to advise them.

What unites these points is an inability to distinguish between objectivity and political views which are so deeply held that Webb is unconscious of them. These assumptions are a constant with Justin Webb. I have noticed them for a long time. When I hear a particularly brazen one I listen to it on iPlayer and transcribe it. What follows is a selection of Webb’s most revealing unconscious lapses.

Exhibit 1 – In which our hero says that all artists are left wing (8 November 2013)

For some reason the Today Programme ran a story on an exhibition of “left wing art” at the Tate Gallery in Liverpool. Selection of this exhibition for a long discussion on Today is already a little questionable. More dubious is what came after arts correspondent Will Gompertz’s survey of purportedly “right wing art” in response to a question from Webb. Webb responded by saying (I quote):

Isn’t there a danger of over-intellectualising? … Art challenges and it challenges the status quo, and if you’re left wing that’s what you do, and if you’re on the political right generally and you’re a conservative you like things as they are.

By saying that art challenges, and challenging is what you do if you’re left wing, Webb implies that all art is left wing. Furthermore, the inescapable logical conclusion of his statement is that the conservatives who “like things as they are” can’t be artists. This is an extraordinary thing to say. Webb’s assumptions about art, when taken at face value, are an undisguised expression of left-wing bias.

As an aside, the exhibition was devoted to artists who not only held “left wing views” – independently of their artwork – but also tried to integrate those views into the way they worked. Webb’s comments by contrast seem to refer to “left wing art” as “art by left wing people,” not as art with specific left wing characteristics as featured in the exhibition. This vagueness in Webb’s terms of reference patronises art; it wouldn’t have been allowed if he was discussing economics, or foreign policy.

But what Webb may say is that the view that “art challenges … and if you’re left wing that’s what you do” wasn’t his personal view, but a view that was held widely enough to be put up for debate on Today. If that were really the case however, one could argue that he should have prefaced his statement with “some people might say” or an equivalent disclaimer. The fact that he did not preface it in this way would strongly suggest a sympathy for the view he was introducing to the debate. But in an effort to be as fair as possible to him you could assume that, perhaps, in the heat of the moment, he just forgot. If we accept this excuse, you could then say that by putting this view to Will Gompertz he was only doing his duty as an impartial presenter.

But even if you accept this excuse, Webb’s assertion would still be very revealing about the views – views regarding art or politics or anything else – which are ambient in Justin Webb’s world, which are part of his mental furniture as it were. It is also revealing in what it tells us about which of those ambient views he naturally cites when presenting on the Today programme. To understand what the selection of this particular notion tells you about Webb you need to make a number of judgements about it: how reasonable is it? how widely held is it? to what extent does it deserve to be a kind of default assumption? If it is normal and rational to hold such a view, then the fact that Webb introduced it to the debate shouldn’t raise any eyebrows. If however it is a flaky view, or one held only by a particular segment of society, then it tells you a lot about Webb’s politics.

The first thing to say is that it is difficult to imagine anyone with any artistic sensibility entertaining anything so absurdly reductive and simplistic as the notion that artists “challenge the status quo.” How does Michelangelo’s David challenge the status quo? Or the Farnese Bull? Or the figs on the walls of Oplontis? Or Velasquez’s Las Meniñas? Or a Chardin still life? Or Anthony Gormley’s Angel of the North? Or Anish Kapoor’s Flaying of Marsyas? Or Rachel Whiteread’s resin blocks? Great art is certainly original, but that originality can form part of the established order as easily as it can challenge it. Such a perception of art is narrow, superficial and lacking in historical perspective.

Webb’s claim about conservatives liking “things as they are” is almost as silly as his assumption that artists “challenge the status quo.” Will Gompertz had only just seconds earlier referred to the Futurists, who both supported the Fascists and wanted contemporary art to make a clean break with its past by embracing the machine age – evidence which contradicted Justin Webb’s very point. Even someone with a very basic knowledge of art history knows that there were always stylistic innovators with right wing politics (Cézanne in his late work) and left wing painters with a rigidly traditionalist approach (such as the Soviet realists); that artists of very different political persuasions can make very similar art, and ideological bedfellows can make very different art (e.g. Malévitch versus the Soviet realists).

What is most reprehensible in Webb’s decision to advance this particular view on the Today programme is not the politics behind it, but how thin and vacuous it is. Serious and analytical left-wing writers on art like Slavoj Žižek, or Georges Bataille, or Walter Benjamin would grimace at such a sub-sophomore offering.

Furthermore, far from being a common view, the idea that conservatives like things as they are is a very particular and determined one. Parties which style themselves as left wing like to portray their views as “progressive” and their opponents as stuck in the past. But the reality is more complicated. The policies of the post-war Labour government were undoubtedly innovative and ground breaking, but more recently it is “the right” which is proposing radical changes such as the introduction of private sector involvement in schools or reductions to certain benefits, and “the left” which wants to “keep things as they are.” Indeed, some artists in the exhibition like William Morris were “left wing” partly because they tried to keep alive the old methods of craftsmanship in the face of the absolutely revolutionary phenomenon constituted by industrialisation and the machine age. So the “left wing art” in the very exhibition Justin Webb was discussing was dedicated to keeping things as they were before the industrial revolution. But Webb wasn’t really paying attention, and that is the point. His views are so deeply ingrained that even the most obvious evidence does not have any impact on them

Webb’s assumption about left wingers challenging the status quo and artists being left wing is representative of a lazy and casual prejudice which is particular to a very specific part of the political spectrum. It really has no place on a serious radio programme. The fact that Webb chose to air it on Today shows that he has internalised this particular left wing view of the world so deeply that he wasn’t aware of it. It just came out, like a repressed desire in a Freudian analysis session.

Webb may say he was being light-hearted. This is not a valid excuse. First because if it is a joke then it’s a really, really poor one and completely unfunny. Second because the Today programme is not a place and art is not a subject for weak jokes. Thirdly because the comments can only be construed as light hearted in a particular context of shared assumptions; if it is a joke then it’s a knowing joke. Saying that it’s light-hearted merely confirms that Webb assumes that everyone thinks like him about the left and its relation to art. Webb presented his very political view on art as an alternative to “over intellectualising” from Gompertz. In so doing he implied that his views were a kind of plain, simple or obvious truth. This assumption shows how deeply seated his prejudices are, and how blind to them he is.

Exhibit 2 – In which our hero refers to the “progressive” vote (29 April 2015)

As part of the General Election campaign Webb visited Bath, where he accompanied the eventually unsuccessful Labour candidate Ollie Middleton as he canvassed voters. His report included a recording of Middleton’s pitch to a young lady who had voted tactically for the LibDems in the previous election. After Middleton’s pitch Justin Webb asked the voter:

Can I just ask you before we go, if your heart is Labour, but you voted LibDem last time, do you feel that the experience of the coalition government has sort of freed you to vote with your heart this time round?

The voter responded “yeah” she had voted tactically before but might not do so this time. Webb asked Middleton: “That was quite encouraging for you?” to which Middleton naturally agreed. Webb then went on to say:

That’s your hope isn’t it because this city actually has quite a lot of people who would regard themselves as progressives [my emphasis], on the sort of liberal left [my emphasis], your big hope is that you kind of peel people away and say vote with your heart now.

To be fair to Webb it is legitimate for journalists to follow candidates (as long as they follow candidates from both sides). And the premise for his story – that those who wanted to vote Labour, but voted tactically for the LibDems instead as the only party likely to beat the Conservatives, may now vote Labour because the LibDems entered a coalition with the Conservatives – was logical after a fashion. But it bore little resemblance to electoral reality in Bath, where, despite a loss of share for the LibDems similar to what they experienced nationwide, Labour ended up with less than half the LibDem vote and the Conservatives won the seat.

But note Webb’s unguarded use of the word “progressive.” As with his equally unguarded comment on artists, he explicitly equates “progressive” with the “liberal left” in this statement. Webb assumes that being left wing is “progressive” the way he assumes left wing artists challenge the status quo. He unconsciously accepts the left’s idealistic self-image which, as we saw, is simplistic and historically inaccurate. Indeed, for Webb a vote for the left is a vote “with your heart,” presenting a vote for Labour as the idealistic option. That may be how Labour sees itself, but Labour is a political party, not a journalist. What is revealing here is that Webb adopts the trope of liberal left = progressive = idealistic without a second thought. Seemingly unconsciously, he organises the world in his reports according to distinctively left wing premises.

And in this throwaway line Webb reveals a belief that there are “quite a lot” of progressives in Bath, in other words that the “progressive” agenda he subscribes to unconsciously is a popular one. He assumes that LibDem voters in Bath are more likely to vote for Labour and will be opposed to the Coalition. That assumption implies the possibility of an untapped reservoir of left wing voters who can shift the electoral balance in the country. In so doing Webb proved himself to be subject to the same wistful thinking as the Labour party was prey to when it thought it could win the General Election. But on what statistic could he possibly have based his “quite a lot”? Is there really a survey showing the number of progressive people in Bath? As it turns out, in the only statistic that counted, namely the General Election, Webb’s “quite a lot” was not discernible (UKIP gained 4.3% points of share compared to 6.3% for Labour), and to this day probably only exists in the world of his unconscious assumptions.

Exhibit 3 – In which our hero interviews Frances O’Grady and asks no challenging questions (28 August 2014)

Webb interviewed Frances O’Grady about a TUC report which found that in some regions most women working part-time were earning less than the living wage (the report referred to the Living Wage as set by the Living Wage Foundation, and was published long before the Conservative government’s proposed increased minimum wage was branded a “living wage” by them). On air, O’Grady said that this was true of “three quarters of women working part time in Lancashire [and] two thirds of part time women workers in West Somerset.” Here is a transcript of the “interview” with Webb’s questions in full:

Now you’re demanding employers do something about this aren’t you but first off let’s be clear, what’s the difference between the living wage and the minimum wage, Frances?

What are the rates in Britain?

(O’Grady gives the factual answers to those questions)

Webb: So you’re finding that it’s overwhelmingly women working part time who earn less than those figures?

O’Grady: women bringing “vital money into the family […] are paying a high pay penalty.”

Webb: Now this comes on top of other figures which show women have suffered more economically during the downturn. Why is it that women seem to consistently come off worse?

O’Grady: Well I think there’s a problem about where women tend to work and the value that’s given to the jobs that women do like care, like cleaning, catering, shop work and so on. But there’s a real problem of attitudes too and I think it’s not just employers who need to get their act together. I would like to see government taking a lead and declare all its departments a living wage employer.

Webb: And this actually, umh, this comes against a background of a long squeeze in real wages as we were hearing a moment ago for all workers doesn’t it?

(O’Grady answered that it was the longest wage squeeze in a century).

Webb: So what can be done? How can we, how can we improve wages for part time women workers?

O’Grady: Well government [should] lead by example like every department signing up to the living wage, but perhaps more importantly government using its public contracts worth £140bn in total to spread the living wage into the private sector. We’d like a higher national minimum wage. But we’d also like to see government and employers recognise that collective bargaining is the best way to get fair wages, but one other issue is that too often we see part time work concentrated in those low wage ghettos, why not have more part time job share and flexible opportunities in the top jobs that pay well?

Webb: But that wouldn’t address the problem for these people ehm working you know … in low paid jobs would it?

O’Grady: No and that’s why we’ve been arguing for a higher minimum wage in those industries like cleaning where we have the evidence that employers can afford to pay more.

Webb: Excellent – Frances O’Grady.

O’Grady: And thank you, Justin.

Every one of Justin Webb’s questions is sympathetic and opens with statements which support a distinctive political narrative. Women are victims of pay injustice (“overwhelmingly women working part time earn less”); women are victims of the economy (“women have suffered more economically during the downturn”); workers in general are victims of the economy (“this comes against a background of a long squeeze in real wages”); and something must be done to redress these wrongs (“how can we improve wages for part time women workers?”). The statements made by Webb as introductions to his questions would not be out of place in a Momentum manifesto! These statements, I remind you, are made by Webb the BBC interviewer and not by O’Grady the TUC interviewee.

More shocking than what he says though is what he doesn’t ask. There is not one single challenging question in the whole interview. And this in an interview where there is much, much to challenge:

- One might point out to Frances O’Grady that women working part-time earn less than the living wage in many regions because there are not many jobs there;

- That if businesses in those regions were forced to pay higher wages they might not be able to afford to hire as many part-time staff;

- That the only alternative to part-time jobs paying below the living wage for many women in those regions is unemployment;

- That companies paying employees high wages are unlikely to get value for money if those employees work part-time

- That countries where governments interfere in the Labour market in this way and enforce higher wages (e. g. France and Italy), as demanded by O’Grady, have high unemployment, with many of their citizens coming to work in the UK labour market criticised by O’Grady as a result;

- That it is unfair to ask tax payers to fund wages in the public sector which they cannot earn themselves in the private sector;

- That it is indeed a little underhand to use people’s natural sympathy for part-time women workers to agitate for a massive pay increase for public sector workers (many of whom are TUC members);

- I could go on …

Of course many will disagree with these points. That’s democracy. The problem is that Webb did not ask a single one of these questions. His only “challenge,” namely that increasing the proportion of part-time workers in high paid jobs “wouldn’t address the problem for [those] in low paid jobs” is a fake question, a lay-up: O’Grady had already answered that question in her previous point! In the end the interview was barely worthy of the name. It turned into a political broadcast by the TUC. It was like a CEO interview in a corporate newsletter, or the questions loyal MPs ask ministers in their party – “And does my Right Honorable friend not agree with me that overwhelmingly women working part time earn less?”

Again, I’m sure Webb is not deliberately biased. But the statements he makes in the lead up to his questions, and his total and abject lack of critical questioning, demonstrate just how deeply he shares O’Grady’s views. Again, this is probably completely unconscious. Webb can’t imagine anyone disagreeing.

The left wing art discussion and this interview both feature subjects on which it was easy for Webb to feel he was doing his bit for causes which the BBC likes to champion – women’s issues and the arts. Perhaps it’s because of this that Webb suspended his critical faculties. He didn’t need to ask difficult questions because he was already earning brownie points by talking about the gender pay gap and about progressive art. But this prevented him from doing his job in the interview with O’Grady, which is to ask the questions to which his audience wants to hear answers. There is a term for this: it is called “virtue signalling.” In both cases, Webb doesn’t analyse the issues but uses them to broadcast his “progressive” views on subjects which make people in the BBC feel warm and fuzzy.

And what a way to end his interview with “Frances” (in which the use of the first name only already betrayed a cosy familiarity): “Excellent.” “Excellent”? Why doesn’t he just give her a round of applause?

Justin Webb’s latest remarks about objectivity show that he cares about journalism as a profession. But it also shows that he is incapable of objectivity, and has been for a long time, possibly since birth. He means well. But his perception of reality is so deeply conditioned by his politics that he is unaware of his bias, which is probably incurable.