A US Appeals Court has rejected an attempt to damage and control the internet provider market. Or, as the BBC put it yesterday:

Net neutrality threatened by court

Which is it, then? Since this is the BBC and a US issue, it’s a good bet that it’s not what the BBC is telling you. First, here’s the BBC’s explanation of what the “Net Neutrality” rules created by the FCC:

Net neutrality is the principle that ISPs should not block web traffic for customers who pay less to give faster speeds to those who pay more.

Sounds pretty reasonable, no? But is it really the goal of the FCC’s rules? We’ll leave for another time the debate about how this is another example of how federal departments are now essentially a fourth branch of government, enacting laws and making legal decisions on their own, outside the three official branches of government. The BBC wouldn’t be interested in that anyway. The BBC’s report continues:

Supporters of net neutrality said the ruling was a major threat to how people use the internet.

The rules were designed to ensure that small or start-up organisations had as much chance of reaching an online audience as a large, established company.

But broadband providers argue that some traffic-heavy sites – for example, YouTube or Netflix – put a strain on their infrastructure.

They say they should be able to charge such content providers so that users who pay more can get faster access to those sites than other customers.

As a consequence, companies who did not pay would find that access to their services could be slower for customers.

It might have been helpful for the reader to appreciate this in the proper context if the BBC had included the background information that YouTube and Netflix account for around half of all internet traffic during peak hours. In fact, Netflix shares dropped a few percentage points after the decision was announce, as investors speculated that this would eventually have an adverse affect on profits. And it’s only going to get worse as Netflix starts adding 4K content and more and more YouTube videos and content on other popular streaming services like Twitch.tv and LiveStream are in higher definition, requiring more and more bandwidth. At some point, something will have to give, and unpleasant decisions will have to be made.

But is it really about “fairness”? Wise people get suspicious whenever that term is used, as it often turns out to mean a highly selective set of beneficiaries.

Verizon had said in September 2013 that if it were not for net neutrality rules they would be looking at different pricing models.

In a statement released after the ruling Verizon said that the court’s decision would not affect customers’ ability to access and use the internet as they do now.

“The court’s decision will allow more room for innovation, and consumers will have more choices to determine for themselves how they access and experience the internet,” it said.

This is more or less true, although there’s a caveat. In reality, consumers are already paying more in some areas because the ISPs have to make up the revenue somewhere else. My own ISP offers consumers a choice to pay $10 more per month for higher speed and more bandwidth. The same people who are in favor of this “net neutrality” rule are against tiered pricing as well, and for the same fundamental reason. I’ll get to that reason later. Some ISPs cap their customers’ bandwidth usage, and some deliberately throttle it during peak hours or when doing a certain type of activity. Which type of activity is likely to get throttled? The voice the BBC provides as standing up for freedom and fairness is the giveaway:

The boss of BitTorrent – a system for sharing large files using peer-to-peer technology – warned that the court’s decision would be a major threat to innovation, free speech and “the internet as we know it.”

“For the ISPs, it’s a momentous decision. This ruling will consolidate their powerful role as arbiters of culture and speech.

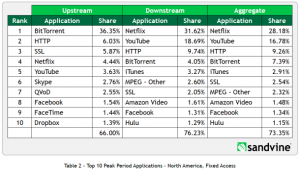

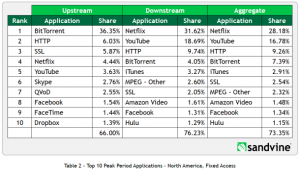

Why the choice of BitTorrent here, which is used largely to distribute pirated content, as the voice for freedom? It could be because BBC journalists not involved in the business side of protecting property rights see them as heroes in the way most BBC staff see Julian Assange and the Occupy movement as inspirations. There’s another key bit of background information which didn’t make its way into the report. This graph says it all:

Source: Sandvine

BitTorrent still accounts for more than a third of uploading bandwidth. The article where I found this graph has a little more pertinent information:

Meanwhile, file sharing continued emaciating on many fixed-access networks as streaming video options like Netflix, YouTube, and others proliferate.

File sharing now accounts for less than 10 percent of total daily traffic in North America, down from the more than 60 percent it netted in Sandvine’s first Global Internet Phenomena Report released more than 10 years ago.

Five years ago, it accounted for more than 31 percent.

ISPs have been throttling torrent use for some time now. That’s the freedom BitTorrent and their advocates are really worried about, and the thought of having to pay ISPs for people to use the technology will be a nearly final blow. The BBC really should have pointed this out in order to paint a more honest picture of the debate their presenting.

Our favorite “Echo Chambers” feature has weighed in as well. (I’ve given up my experiment on that for the moment, pending a rethink.)

The concept, called net neutrality, has been the source of a great deal of debate – in the US Congress, courts and the media. Supporters view it as a way to ensure freedom and fairness on the internet, while opponents call it unnecessary government intrusion on business.

There’s that word again: “fairness”. The editor, Anthony Zurcher, first offers the conservative, anti-government regulation point of view from the Wall Street Journal. That view is essentially that it makes no economic or legal sense to prevent ISPs from charging more for more use of their service than it would to prevent a retailer from charging more when somebody buys more than one item. This kind of damper, they say will also impede other providers from getting involved because their chances of getting a return on their investment is severely curtailed.

Also from the Wall Street Journal is an op-ed from the former FCC commissioner, Robert McDowell, who says the whole thing is a bad idea because there are already plenty of measures in place to protect freedom. He’s been a staunch opponent of government meddling with the independent commission and attempts to get around legal infrastructure for some time. Furthermore, he says, more regulation could pave the way for a global body to try and regulate everything, which would ultimately place at least parts of it under the control of those who seek to crush freedom. That’s the part of his piece Zurcher feels was important to cite, anyway. I, on the other hand, think the bit immediately preceding it is more worthy of your attention:

But the trouble is, nothing needs fixing. The Internet has remained open and accessible without FCC micromanagement since it entered public life in the 1990s. And more regulation could produce harmful results, such as reduced infrastructure investment, stunted innovation, slower speeds and higher prices for consumers. The FCC never bothered to study the impact that such intervention might have on the broadband market before leaping to regulate. Nor did it consider the ample consumer-protection laws that already exist. The government’s meddling has been driven more by ideology and a 2008 campaign promise by then-Sen. Barack Obama than by reality.

What ideology could that be, you ask? McDowell has been fighting against this for quite some time. Zurcher doesn’t want you to think about that. Instead, to balance out the two opinions from the Right-wing echo chamber (which are really the same opinion, albeit one has the appeal to authority), we get the notionally impartial Yahoo blogger, a venture capitalist with a vested interest Zurcher forgets to point out, and his usual collection of Left-wing Progressive voices: Slate, Ezra Klein, and Juan Cole, the latter of whom is way, way out there on the far-Left fringe.

The best point from that side is the only one that comes close to something resembling fairness. It seems reasonable to worry that, as we’ve all become so spoiled by fast speeds that we’re wont to click away when something doesn’t load instantly, and choose faster loading sites over slower ones, the little guys will be harmed, and the internet won’t be an even playing field because they can’t pony up like the big boys can. Of course, that’s most likely not going to be the case as the ISPs are only going to try to squeeze the big boys, as the little guys aren’t using up all the damn bandwidth. More moaning about “preferred access” crushing new ventures and Rupert Murdoch’s “growing power” (like Mrs. Thatcher, he’s never far from a Beeboid’s thoughts, is he?) won’t change that.

If the point of this installment of “Echo Chambers” is to unscramble the noise, you can see which side of the debate the editor feels is the best one. As always, it’s of the Left.

Zurcher or the writer of the BBC Technology article could have offered another point of view, one that suggests this ruling isn’t really bad at all because it actually acknowledges that the FCC has more power to force behavior on ISPs. It’s from the Left-leaning Los Angeles Times:

The appeals court ruling Tuesday that rejected most of the Federal Communications Commission’s “net neutrality” rules sent a fair number of Internet advocates into panic attacks. But the worst-case scenarios laid out in the media — consumers gouged, rival websites blocked, commercialization triumphant — are for the most part overblown.

That’s because the ruling was actually a victory for the methodical rule-making process conducted by former FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski (shown in an unflattering photo above). In sharp contrast to his predecessor’s attempt to force broadband Internet providers to treat all legitimate traffic on their networks equally, Genachowski’s rules weren’t thrown out wholesale.

In fact, the court held that the FCC established that it did indeed have the authority to protect “edge providers” — that is, websites, services and uploaders — against mistreatment by broadband Internet service providers. What the court rejected were the specific rules the commission adopted to preserve openness online.

So it’s perhaps not quite the blow to “fairness” and “freedom” that all those from the Left-wing echo chamber claim. It’s a very complicated web (sorry) of services, technologies, and markets (the latter is a real problem regarding monopolies and fairness and harm to the consumer, but that’s another topic) and the author, John Healy, is aware that this might open the doors for ISPs to weight their services toward more profit-making content, but also says that history tells us that consumers and technology won’t put up with restricted freedom and choice for very long. He suggests it’s in the best interests of everyone for the ISPs to work something out that isn’t too restrictive. Why Zurcher decided to go with his usual opinion-mongering suspects instead of this more measured voice I have no idea. Maybe the LA Times isn’t in his echo chamber feed.

Getting back to the true reason behind all this, I’d suggest a different analogy about the folly of preventing ISPs from charging more from the one the WSJ editorial offered, perhaps one the BBC is more likely to understand. Preventing ISPs from charging more when more of their service is used would be like preventing Hertz or Avis from charging more when somebody rents a BMW rather than a Ford Focus. In this case, the rental company certainly can’t force BMW to lower the cost to get the car into their fleeet, so they have to pass that on to the consumer. Nobody complains about this because it’s obvious, up front. “Net neutrality” would similarly prevent ISPs from charging Netflix or Google (YouTube) more for offering their products, so they will continue to have to pass the expense on to the consumer.

And therein lies the true reason behind this whole thing. Behold:

The Origins of the Net Neutrality Debate

Telecommunications companies and their suppliers have been nursing dreams of tier pricing for years.

I mentioned tier pricing earlier, and here’s where it gets interesting. By the way, this is from 2006.

On June 28, the Senate Commerce Committee rejected amendments that would have built a ban on tiered pricing for Internet access into the big telecommunications bill Congress is trying to pass this session. It was a big blow for “net neutrality” advocates, who argue that if the major cable and telephone companies are allowed to sell certain customers faster Internet connections, those who can’t afford the new tolls will be relegated to the slow lane.

I think you can see where this is headed, no? John Fund wrote the following article in 2010 in that apparent bastion of the Right-wing echo chamber, the Wall Street Journal:

The Net Neutrality Coup

The campaign to regulate the Internet was funded by a who’s who of left-liberal foundations.

I’m sure you’re all shocked, shocked to learn that.

The Federal Communications Commission’s new “net neutrality” rules, passed on a partisan 3-2 vote yesterday, represent a huge win for a slick lobbying campaign run by liberal activist groups and foundations. The losers are likely to be consumers who will see innovation and investment chilled by regulations that treat the Internet like a public utility.

There’s little evidence the public is demanding these rules, which purport to stop the non-problem of phone and cable companies blocking access to websites and interfering with Internet traffic. Over 300 House and Senate members have signed a letter opposing FCC Internet regulation, and there will undoubtedly be even less support in the next Congress.

Yet President Obama, long an ardent backer of net neutrality, is ignoring both Congress and adverse court rulings, especially by a federal appeals court in April that the agency doesn’t have the power to enforce net neutrality. He is seeking to impose his will on the Internet through the executive branch. FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski, a former law school friend of Mr. Obama, has worked closely with the White House on the issue. Official visitor logs show he’s had at least 11 personal meetings with the president.

Like with the IRS scandal, we keep learning about these bosses of allegedly independent departments having lots of meetings with the President just before that department launches an obviously ideological initiative. However, I should also point out that Genachowski worked with McDowell for years, and he, too stepped down last year. McDowell, as it happens, praised his colleague when the former announced his departure, while acknowledging ideological differences. So perhaps he’s not quite as bad as Fund alleged. As for the ideology in question:

The net neutrality vision for government regulation of the Internet began with the work of Robert McChesney, a University of Illinois communications professor who founded the liberal lobby Free Press in 2002. Mr. McChesney’s agenda? “At the moment, the battle over network neutrality is not to completely eliminate the telephone and cable companies,” he told the website SocialistProject in 2009. “But the ultimate goal is to get rid of the media capitalists in the phone and cable companies and to divest them from control.”

A year earlier, Mr. McChesney wrote in the Marxist journal Monthly Review that “any serious effort to reform the media system would have to necessarily be part of a revolutionary program to overthrow the capitalist system itself.” Mr. McChesney told me in an interview that some of his comments have been “taken out of context.” He acknowledged that he is a socialist and said he was “hesitant to say I’m not a Marxist.”

Sounds like he’d fit right in at the BBC. Read all of Fund’s piece to get the full picture of the ideology McDowell was worried about. This is the true goal of the whole “net neutrality” thing: to put a stop to evil corporate capitalist profits, period. After all, first the advocates wanted to prevent ISPs from charging customers more for using more of their service, then they wanted to prevent ISPs from charging content providers for placing a higher burden on their services. The only goal of either approach is to prevent profits, no matter how much it’s dressed up as consumer advocacy and “fairness”. Instead, the BBC hides this from you and frames it in a “fairness”, David vs. Goliath context, just like all the Left-wing echo chamber voices Zurcher quotes.

Zurcher is a titled editor. In that sense, he operates on his own, and while he has a supervisor on some level he is not, so far as I’m aware, subject to editorial directives from on high, or from anyone else which might direct him to publish something reflecting the same point of view as the BBC Technology journalist who wrote the first piece I cited. The bias happens naturally, because they all think the same way. An echo chamber, indeed.